DNA sequencing in horses and microdiversity trapped in ancient salt crystals seem to have very little in common, but one Binghamton University undergraduate dipped into both areas of research during her time on campus.

DNA sequencing in horses and microdiversity trapped in ancient salt crystals seem to have very little in common, but one Binghamton University undergraduate dipped into both areas of research during her time on campus.

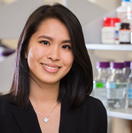

Senior Alice Cheung’s dedication to her studies and research is evident through more than just her 4.0 grade point average in cellular and molecular biology. “I was really intrigued by being able to focus on one part of the science,” she says, “and finding out something that no one else has done before.”

Cheung, who is originally from Queens, began her research experience at Binghamton in the lab of anthropologist J. Koji Lum. Lum, who has worked with more than 100 undergraduate researchers, says Cheung stands out for her hard-working attitude and ability to learn quickly.

The project was a collaboration of researchers in anthropology, geology and biology. Cheung’s role was to characterize gypsum crystals according to the microdiversity trapped inside of the salt during its formation. The identification of these organisms would provide the team with information about what the environment was like when that crystal formed. The team then used the same technique and applied it to ancient crystals, hoping to find more clues about what life was like millions of years ago.

The team’s abstract was published in The Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. Cheung also presented her findings at an international conference, a rarity among undergraduate researchers.

In the lab, Cheung would extract and sequence DNA from the modern crystals and compare her results with her partner, a geology major, who confirmed the findings under the microscope. When they looked at the ancient crystals, however, they weren’t able to find the same results.

Lum and his team of graduate researchers discovered that what they were originally looking for could not be found. “Although her project did not turn out as hoped,” Lum says, “I think it was a valuable lesson in how science often really works.”

In science, a dead end is really more like an open door. Cheung learned that lesson firsthand when she began working in a new lab with Steven Tammariello, an associate professor of biology. His team uses DNA from horse hair samples to screen for desirable genetic traits.

Cheung is trying to find the short fragment of DNA that codes for jumping ability in horses. The offspring of horses that can jump do not necessarily share the trait, so this science could eventually help horse buyers determine if a horse will be a good fit.

This same science can be applied to sequencing human DNA. Scientists are now able to screen DNA to see if someone is prone to diseases such as Alzheimer’s, which can help a person seek appropriate and timely treatment.

“I did research to help me decide what it was I wanted to do in life,” Cheung says.

And it did just that. Cheung plans to attend medical school and continue participating in research.