At the end of a long day spent moving to a new home, a woman felt a pain in her chest so severe that she dropped to the floor. A man might have called 911, but the woman assumed that this could not be a heart attack. “Women don’t have chest pain like men,” she later told Pamela Stewart Fahs. So she just stretched out until she felt better.

At the end of a long day spent moving to a new home, a woman felt a pain in her chest so severe that she dropped to the floor. A man might have called 911, but the woman assumed that this could not be a heart attack. “Women don’t have chest pain like men,” she later told Pamela Stewart Fahs. So she just stretched out until she felt better.

But chest pain can signal a heart attack in a woman. Women also may experience a range of other symptoms, not all of them easy for the typical sufferer to identify.

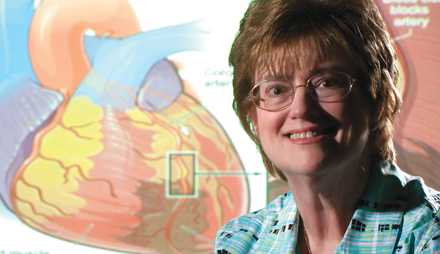

“We believe that heart attacks in women go unrecognized 30 to 55 percent of the time,” says Stewart Fahs, professor and Decker Chair in Rural Nursing at Binghamton University’s Decker School of Nursing. Women who miss the warning signs fail to get help, or they head for the hospital only when the problem grows acute, increasing the risk that they will die or be gravely disabled.

In hopes of shortening women’s time to treatment, Stewart Fahs is collaborating with Melanie Kalman, associate professor and director of research in the College of Nursing at SUNY Upstate Medical University, on a project called “Matters of Your Heart.” The goal is to develop an effective program to educate women about heart attack symptoms and also to teach about the early warning signs that a heart attack might be on the way.

Heart disease is the No. 1 killer of women. In fact, 1 in 4 women in the United States dies from heart disease, according to the National Institutes of Health. The most recent national study on the subject, however, found that 49 percent of women don’t realize that they need to be concerned about heart disease, Stewart Fahs says.

That number is lower than in past years, and the medical community has gotten out the word that women’s heart attack symptoms may differ from men’s. However, as the story of the woman on the floor points out, there’s still room to improve education about women’s cardiovascular disease.

Intense pain might be the first obvious sign of an impending heart attack, Stewart Fahs says. But many women who look back on the period before an attack report that they first felt pressure or discomfort. “Some women will say, ‘It’s like I had a big knot up here,’” she explains, pointing to her upper chest. “‘Like I swallowed an orange whole.’” Overwhelming fatigue or pain that radiates into one or both arms or the neck or jaw are other common warning signs.

Intense pain might be the first obvious sign of an impending heart attack, Stewart Fahs says. But many women who look back on the period before an attack report that they first felt pressure or discomfort. “Some women will say, ‘It’s like I had a big knot up here,’” she explains, pointing to her upper chest. “‘Like I swallowed an orange whole.’” Overwhelming fatigue or pain that radiates into one or both arms or the neck or jaw are other common warning signs.

Kalman and Stewart Fahs conducted the first phase of their project under an intramural research grant from SUNY Upstate. Their first task was to develop a questionnaire to measure a woman’s knowledge of heart attack symptoms and warning signs. They then created a pilot version of an educational presentation.

Working with 141 post-menopausal women, Stewart Fahs and Kalman held small-group sessions to administer the questionnaire, present the program and then give the questionnaire again. “We did find that the educational program increased knowledge,” Stewart Fahs says.

The researchers based the presentation in part on a program that Stewart Fahs developed several years ago to teach rural residents about symptoms of a stroke. That program employed an acronym created by the American Heart Association — FAST, for Face, Arm, Speech and Time.

The new program uses a similar mnemonic device, and Stewart Fahs says the method has proven effective, especially when women practice putting it to use. “We have periods in the presentation when they work in groups of two to four and come up with different symptoms for heart attacks and the female warning signs,” she says. Members take turns naming the symptoms.

As a specialist in rural nursing, Stewart Fahs gave the questionnaire and program to women in rural areas, while Kalman concentrated on urban Syracuse. The population they have studied so far is too small to reveal whether the program works better for one demographic or the other, Stewart Fahs says.

In a second phase of their research, Kalman and Stewart Fahs plan to give the presentation to many more women over a broader geographical area. Eventually, they hope to do a longitudinal study to discover whether their program improves the way women respond when they experience signs of a possible heart attack. “Having knowledge doesn’t necessarily change your behavior,” Stewart Fahs says. “But if you don’t have the knowledge, you’re unlikely to change.”

Once they’ve perfected the program, the researchers will share it with hospitals, community health agencies and other healthcare organizations. Besides offering the PowerPoint slides for classroom use, they might someday use communication technologies to give the presentation a broader reach, Stewart Fahs says. “There should be a way, through cell phone apps or some kind of Internet application, to get this message out to women once it’s fully developed and tested.”

While looking for new ways to educate women about heart attacks, Stewart Fahs also continues helping to advance the discipline of rural nursing. In May, she became editor of the Online Journal of Rural Nursing and Health Care. She also serves as an external advisor to the Interdisciplinary Healthy Heart Center: Linking Rural Populations by Technology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Her combined expertise in rural nursing and cardiovascular issues makes Stewart Fahs especially valuable as an advisor to the Healthy Heart Center, says Professor Carol Pullen, principal investigator on the project. One striking aspect of Stewart Fahs’ work is that, along with publishing articles on cardiac risk among rural women for academic journals, she also writes for media that reach a wider audience, Pullen says. “I think it’s important not only to get your work in scientific journals, but also to get it out to lay publications for everybody to enjoy the results of your research.”

Stewart Fahs hopes that the results of her latest research will include better outcomes for more female victims of heart attack. “The more aware you are of the signs and symptoms,” she says, “and the more aware you are of the risk of heart disease for women, the better able you are to take a proactive stance.”

Who is at risk

Certain factors make it more likely that you’ll develop coronary heart disease and have a heart attack. You can control many of these risk factors.

Major risk factors for a heart attack that you can control include: Smoking, high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, obesity, an unhealthy diet, lack of routine physical activity and high blood sugar due to insulin resistance or diabetes.

Risk factors that you can’t control include: Age (the risk of heart disease increases for men after age 45 and for women after age 55 or after menopause), family history of early heart disease and preeclampsia (a condition that can develop during pregnancy).

Although many people think of heart disease as a man’s problem, heart disease is the No. 1 killer of women in the United States. It is also a leading cause of disability among women.

The most common cause of heart disease is narrowing or blockage of the coronary arteries, the blood vessels that supply blood to the heart. It’s the major reason people have heart attacks. Prevention is important: Two-thirds of women who have a heart attack fail to make a full recovery.

Source: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Knowledge about this is extremely important, it saves lives.

I wonder what the same type of report would find if they looked at rural areas instead of metropolitan. Wonder what kind of difference they’d find then. Good article!