If the future echoes the past, the U.S. economy of the 21st century will be fueled by scientific breakthroughs. The money needed for such research has often come from the federal government. But here the past and the future may diverge. As Congress takes aim at budget deficits, science funding at every American research university is in the cross hairs.

If the future echoes the past, the U.S. economy of the 21st century will be fueled by scientific breakthroughs. The money needed for such research has often come from the federal government. But here the past and the future may diverge. As Congress takes aim at budget deficits, science funding at every American research university is in the cross hairs.

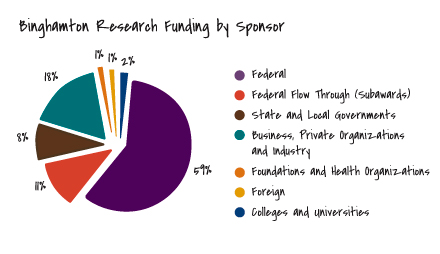

That threat has spurred Binghamton University researchers to look for new funding sources — including private industry, foundations, think tanks, venture capitalists and licensing agreements. One researcher has aligned with scientists at a European university who still have cash to spend. Others plan to scale back the scope of their research if necessary. Federal cash isn’t easily replaced: It has made up more than half of all university research funds in recent years.

“We have faculty who have been funded for 20 years or more who may not be funded,” says Lisa Gilroy, assistant vice president in Binghamton’s Office of Sponsored Programs. “As a state-supported school, we’re feeling it from state budget cuts, too. Sometimes, it’s a twofold blow.”

Major cuts could seriously dent Binghamton’s fast-growing research program. Current research awards of $44 million annually are nearly triple the $15.4 million of just 15 years ago. And research is a machine that requires constant feeding. “It’s personnel, it’s equipment, it’s infrastructure,” Gilroy says. “Research is costly.”

Major cuts could seriously dent Binghamton’s fast-growing research program. Current research awards of $44 million annually are nearly triple the $15.4 million of just 15 years ago. And research is a machine that requires constant feeding. “It’s personnel, it’s equipment, it’s infrastructure,” Gilroy says. “Research is costly.”

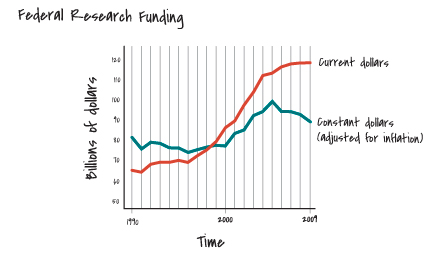

Even before the budget ax began to fall, science funding was in trouble. Although federal science spending had been inching up since 2005, when adjusted for inflation, spending had been falling quickly, according to National Science Foundation reports. In the 2011 fiscal year, federal science spending will fall $5.2 billion from 2010 levels, according to data compiled by the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Most of the cuts will hit defense-related research, but more than a billion dollars will come out of the federal research budget for health, energy, homeland security and agriculture. Much larger science cuts in the 2012 budget are expected if Congress proceeds with proposals to slash trillions of dollars in overall spending.

With that in mind, Binghamton researchers are already in search of new funding. For instance, Jessica Fridrich, professor of electrical and computer engineering, may look to the movie industry to pay for her video technology research. Her technology can be used by law-enforcement officials to trace video back to specific recorders, an innovation useful when tracking bootleggers. Chemistry Professor Omowunmi Sadik may look for venture-capital funding or licensing revenue to support her work in sensor technology. Her sensors could be used to monitor food and water for contaminants, detect weapons of terror or look for diseases such as cancer. Steven Jay Lynn, distinguished professor of psychology, is collaborating with Dutch researchers on sleep-deprivation studies. The Dutch government is providing most of the funding.

With that in mind, Binghamton researchers are already in search of new funding. For instance, Jessica Fridrich, professor of electrical and computer engineering, may look to the movie industry to pay for her video technology research. Her technology can be used by law-enforcement officials to trace video back to specific recorders, an innovation useful when tracking bootleggers. Chemistry Professor Omowunmi Sadik may look for venture-capital funding or licensing revenue to support her work in sensor technology. Her sensors could be used to monitor food and water for contaminants, detect weapons of terror or look for diseases such as cancer. Steven Jay Lynn, distinguished professor of psychology, is collaborating with Dutch researchers on sleep-deprivation studies. The Dutch government is providing most of the funding.

But for some researchers, the money may run out. One is Ralph Miller, distinguished professor of psychology. Miller does basic research in the areas of learning, memory and decision making. Basic research has no immediate commercial application, but it may provide the theoretical underpinnings of future treatments or products.

Though Miller has received federal support for all 32 of the years he has been at Binghamton, the National Institutes of Health has said that he must do more applied research or lose his funding. Applied research is designed to result in new products or treatments relatively quickly. (The NIH is to receive a $329 million budget cut in fiscal 2011.)

Miller has enough money to continue his research for another 2½ years. When it runs out, he will discontinue his costly animal research and will switch to using human subjects. “That’s what I can do without NIH money and still continue the direction of my basic research,” he says.

In any case, the competition for grants will increase. “If the pool of money shrinks, then I have to put in better proposals,” says Patrick Regan, professor of political science. He has used funds from the National Science Foundation, the World Bank and the CIA to model what happens when third parties intervene in conflicts in other nations. His work focuses on hypothetical situations, but the findings have applications today. “Libya is a perfect example,” he says.

With the prospect of less federal funding, Regan is seeking money from the U.S. Institute for Peace, created by Congress in 1984 to promote peace and conflict resolution. He will again try the National Science Foundation. “But if I don’t get funding for any one year, I don’t think my life will change,” he says. “I still have things to do with data I’ve already collected.”

That approach may not work in the life or physical sciences, which have to keep labs running and scientific teams together. “If I were in chemistry and maintained a lab with five post-docs, and my lab shut down, I’d be pretty bummed out,” Regan says.

Federal science cuts will damage the economy as well, researchers say. “What is lost if I can’t fund this work?” Fridrich asks. “That’s the million-dollar question. How much is lost if you can’t obtain intelligence in time to prevent (a terrorist act)? How much is lost if you can’t show a movie pirate created bootleg movies? You can’t really put a price tag on these things.”

At the same time, failing to pay for science now could mortgage the nation’s future. “Science is not a luxury,” the late John Marburger III, former science advisor to President George W. Bush and then-vice president for research at Stony Brook University, wrote in an April 2011 opinion piece in The Huffington Post. “Economists estimate that approximately half of post-WWII economic growth is directly attributable to R&D-fueled technological progress.”

Major cuts would also crimp the pipeline that supplies tomorrow’s scientists. Typically, future scientists learn by serving as undergraduate and graduate research assistants to faculty members. Cut the research budget, and there’s no money to pay them. “I had to let go a post-doctoral assistant,” says Fridrich, who is skimping along on her last remaining research grant.

Having fewer scientists would cost the U.S. heavily, Sadik says. “It would reduce our global competitiveness,” she says. That’s because cuts may not only shut the door on promising American students, but also slash the number of talented foreign students who come to study in the United States.

American industry might pay the biggest price. Universities are bastions of basic research — research that is costly and often doesn’t pay off for decades. In recent years, industry has increasingly looked to universities for the basic-research breakthroughs that lead to new products. Without these innovations, in fields such as physics, chemistry and biology, we wouldn’t have today’s cheap, fast computers, manned space flight or high-tech medicines.

As the crunch hits, some researchers may find cheaper ways to pursue research. There is precedent for economic necessity forcing scientists to think outside the box. The Soviet Union is a key example. It was denied access to advanced Western computers during the Cold War. With no alternatives, Soviets created sophisticated software that enabled scientists to do more with the second-rate computers they did have.

Russian computer scientist Igor Agamirzian described the Soviet system in the April 1991 issue of Byte, one of the leading computer magazines of that time. “My fellow students and I were proud of Soviet software engineering, convinced that there were positive aspects in our dated computer hardware: It was a training factor that enabled us to engineer applications that were better than the American programs. Americans, we thought, did not care about efficiency. But we had to, so we were better programmers.”

The United States has suffered fewer deprivations, and its well-funded science system has helped create the world’s strongest economy. But even in good times, federal money was hardly guaranteed. “I believe the majority of grant proposals are not funded,” Lynn says. “It has always been very tight.” Now things could get tighter still, forcing researchers to make tough choices.

“More than ever, I feel I have to pick and choose the projects I want to do,” Lynn says. “Right now, I’m doing research at Binghamton that can be done without outside funding. If I could get the grants, I would be doing different research. In a sense, tight budgets force people to decide what they can and cannot do. You have to allocate resources, and you have to make every hour of research count.”